History of the Beverly Hills Police Department Shoulder Patch

The Beverly Hills Police Department patch displays the Seal of the City of Beverly Hills. Each symbol depicts the history of Beverly Hills from its settlement to its development as a major commercial and residential community. Depicted in the center of the patch is City Hall, the seat of local government of the City of Beverly Hills. The five-pointed star represents the City Council of five members, the governing body of the City, beginning with the lower left of the patch and divided by points of the star, each symbol depicts a historical period in the development of Beverly Hills. The Eagle holding the serpent represents the period of Mexican sovereignty (1822-1846); the shield of stars and stripes represents the status of the City of Beverly Hills as a city of the United States of America; the Bear Flag represents the California Republic of 1846 and the State of California as one of the United States; the Lion of Leon and the Castle of Castile represent Spanish rule over what is now the State of California.

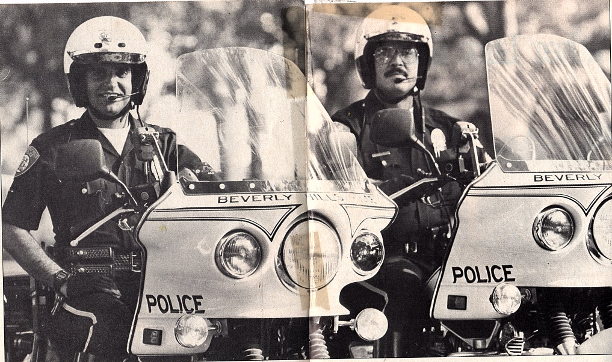

Beverly Hills Cop, Too

Rider Magazine November 1987

By Davis Lester

They’re not nearly as funny as Eddie Murphy, and they work a lot harder for a lot less pay.

Sergeant Munoz-Flores and Officer Carra smiled politely as their picture were being taken. “Ever since the movie Beverly Hills Cop and Beverly Hills Cop II, everyone wants his picture taken with an authentic Beverly Hills police officer,” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said. Neither one blinked as the strobe went off.

“Last night I had my picture taken by people from Japan, Mexico, Ireland and London. We are encouraged to meet the public,” he said as the strobe snapped at him again.

This was my first time I ever talked to a motorcycle officer without trying to explain that, while completely illegal, there were perfectly good reasons for my erratic traffic maneuvers. I didn’t think they could ticket me for impertinence, but I was not going to ask them what they did for a living besides being a photo stop on a Gray Line tour, looking good in a uniform and handing out an occasional ticket. I try to be polite to people with guns, so I started with an innocent question; “What are your duties as motorcycle officers?”

“We are the cavalry of the police department,” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said. “With all of the traffic congestion that we have, a motor officer can get to a scene quicker than a patrol car, the fire department or the paramedics. We spend most of our time splitting lanes.”

“We respond to all emergency calls and traffic collisions as well as doing traffic enforcement, security escorts,” added Officer Carra. “Other cities have motor officers primarily for traffic enforcement, but we respond to all hot call. Traffic is our secondary duty.”

I feel the same way about motorcycle cops as I do about dentists: They are probably nice people, but I hate to see them. Getting a ticket is just as much fun for me as having a cavity filled. I was relieved to learn that not all motorcycle officers spend their days finding obscure sections of the vehicle code to enforce. Beverly Hills may be the only city whose primary concern is not traffic enforcement duty.

Both Officer Carra and Sergeant Munoz-Flores had warmed up to the discussion about Beverly Hills. They volleyed enthusiastic comments back and worth between the. “Beverly Hills is a world-class international city,” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said with pride, and we are very selective about who we choose for motor officers. Most of the motor officers have bachelor’s degrees and the other are working toward them. We only accept those who are good image of the police force.”

“We are involved weekly in something beyond normal police work,” said Officer Cara, continuing the volley. “we work special duty when the President is staying here, we have the Academy Awards, Governor’s Ball, visiting heads of state, we just had the Los Angeles Times Subaru Bike Race run through our streets; there is so much more to the job here then in any other city.”

“Everyday is different. It rejuvenates your enthusiasm for the job,” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said. “I can be giving a little old lady direction to Giorgio’s, and 30 seconds later be in a high-speed chase.”

High speed chase. Steve McQueen in Bullitt. Clint Eastwood in Magnum Force. This is the stuff I was waiting for. It’s what separates the motorcycle officers from the dentists. Motor officers get to ride a motorcycle as fast as they want to without ever getting a ticket. This was my dream come true.

Officer Carra broke that dream with unfortunate reality of what a high-speed chase or response to an urgent call is actually like. “Motor officers have to ride faster than they want to. If I get a call for officer needs assistance; and it is safe to split lanes at say 50 mph, I might be doing it at 60 or 70 mph. It is imperative that I get there as quickly as possible. In an eight-hour day, I’ll have two or three near misses.

“I’ve wrecked two police cycles,” Officer Carra continued. “I was sideswiped by a juvenile-he just changed lanes into me and took me out – and I hit spilled diesel fuel while pursuing a speeder and slide into a truck.”

“Everyone in our department has had at least one accident,” said Sergeant Munoz-Flores. “The most common accident is someone making a left turn in front of you. Most of our riding is done at slow speeds, but a motor officer is always at risk. We feel very fortunate that the most serious accident we’ve had this year is a broken arm. Experience, training and luck minimize the risk, but risk is a part of the job. There are a lot of things that can put you down, and it takes concentration to ride a motorcycle in pursuit while also evaluating the roadway.”

“I’ve had two major accidents in six-and-a-half years as a motor officer,” said Officer Carra, “But I’ve also saved two lives by getting to an accident minutes before the paramedics could arrive. If you can save a life, you have to weigh that against your own safety.”

That last remark took all the Hollywood out of “high speed.” These officers were risking a high-speed slide on skin-eating concrete or a high-speed crash into a garbage truck for people whom they have never met. For them, a high-speed chase is not an adventure, it’s part of their job.

“We ride all the time, eight-hours a day, and through training and experience you develop a sixth sense for dangerous situations.” Said Sergeant Munoz-Flores, “I’ll get a bad feeling about an intersection, and I’ll slow down just as someone will blow the light. I’ve never been wrong about one of these feelings.”

Sergeant Munoz-Flores has plenty of riding experience. His first motorcycle was a Honda 250 Scrambler that he got when he was 16. He worked his way through two Honda 750’s, a Triumph, a Harley Sportster, a BSA and others, and rides an Aspencade to work. “I’ll go for weeks without ever touching a car,” the Sergeant said. “I’ve been riding motorcycles since I was 16, and I considered myself a good rider until I went to motor school.”

All 10 of the Beverly Hills motorcycle officers were required to take a two-week training course given either by the Los Angeles Police Department or the California Highway Patrol. The 80 hours of training are called “motor school.”

“For two weeks, I rode for seven physically and mentally demanding hours every day.” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said. “The first thing they taught me was how to ride a motorcycle slowly, at a walking pace or less. They feel that if you can control a motorcycle at a slow speed, you can control it better at all speeds. I learned what can be done on a motorcycle. We rode up curbs and down curbs. We worked on combination braking, dirt work and roadway appraisal. They teach you the dynamics of riding a motorcycle. I’m convinced that all cyclists should take some kind of training course, no matter how good they think they are.”

“It’s amazing what a police motorcycle can do,” Officer Carra said. “I’ve had everything from little dirt bikes on up. I’ve ridden police Harleys, Hondas, Moto Guzzis and Kawasakis, and I wouldn’t change a thing on the cycles we have now. They came stock from the factory and the only changes we made were the addition of two lights.”

Michael Carra’s long history of motorcycling started when he was 14. Among the 20 or so motorcycles he has owned was a Triumph Bonneville, a Harley Sportster, a Honda CR500, a Kawasaki LTD, and a very mean Yamaha Turbo test bike that ran 14 pounds of boost. “That bike ran like it had two motors,” Officer Carra said with a thinly veiled smile.

Michael’s father was a police officer for 28 years, and retired as a motor officer from the Beverly Hills Police Department in 1981, the same year Michael came to Beverly Hills. Michael now wears his father’s badge – No. 342.

Motorcyclists feel a kinship for one another; they are sharing the same road, the same wet mornings, the same hazards. I asked Officer Carra if there was much difference between riding as a police officer and as a “civilian.”

“When I’m riding off duty,” he said, “I get the feeling that there is a big target painted on my back. People don’t see you when you’re on a motorcycle, but when I put on my uniform and get on a police motorcycle, everyone sees me and moves out of the way. It’s like the parting of the Red Sea. I can ride more aggressively on duty; I have to ride defensively off duty.”

“Riding police motorcycles is a lot like riding touring bikes with stiff suspension.” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said. “They are very comfortable with the upright riding position. The only thing that takes some getting use to are the floorboards. Once you get used to those, they are the only way to go. I put floorboards on my Aspencade after seeing how comfortable they are.”

The Kawasaki KZ1000P that the Beverly Hills police officers ride was designed in the mid- ‘70s by Kawasaki “specifically for police work,” Its motor was designed in 1974, and survives today only in the Police 1000. The KZ1000P hasn’t changed much in the last 10 years and, compared to 1987 models, seems dated and low-tech, with its floorboards and air cooling. It has a dry weight of 595 pounds, a 60.4 -inch wheelbase, and a 30.7-inch seat height. The only modification made are the addition of lights and ergonomic adjustments to suit the officer. The reason that the KZ1000P hasn’t changed is because it works. Officer Carra rides a KZ1000P eight hours a day, five days a week, and he said, “I wouldn’t change a thing on it.”

Many motorcyclists would pay cash to ride around on a Cavalcade with a siren and lights and give out tickets to every dangerous or incompetent driver they could find, but don’t measure your foot for motorcycle officer’s boot just yet.

“Police officers see the best of society and the worst parts of society.” Sergeant Munoz-Flores said, “and it can be really depressing.”

“Dealing with the injured and the dead is the worst part of the job,” Officer Carra said as his face visibly tightened. “It is almost a God-given right to go out and drive foolishly and kill somebody. Fifty thousand people die each year in the United States from automobile accidents. Twenty-nine thousand of those deaths are caused by drunk drivers. Three hundred people are killed in airplane accidents each year, and every time there is a near miss between planes you hear about it on the news and an investigation is underway. You don’t hear about a ‘near miss’ between two cars on Wilshire Boulevard. I see a lot of senseless brutality and death; a lot of carnage, kids hurt, people dying. It’s frustrating, but we are professionals paid to deal with these situations and we can’t take anything personally; the profession won’t allow it. We have very few traffic fatalities in Beverly Hills, only two or three each year, but thought and images linger for years. It hurts.”

Sergeant Munoz-Flores added with a sigh, “I never wanted to be a police officer when I was growing up. I wanted to be an attorney. Not many jobs have your life on the line. I entrust my life to the other officers; it makes for a special relationship. We are like family. We protect each other. I wouldn’t trade my profession for any other.”

“We both grew up in the ‘60’s and there were a lot of negative feelings toward the police,” said Officer Carra. “My father was a police officer for 28 years, and neither one of my parents wanted me to be a police officer. They gave me no encouragement or support, but when I graduated from the academy, there wasn’t a bigger smile then the one on my father’s face. This is my career.”

“Other motorcyclists look at me and think this is the greatest job in the world – riding a motorcycle eight hours a day and getting paid for it.” Said Sergeant Munoz-Flores. “Well for me, it is.”

Well, it isn’t for me. I wouldn’t feel fortunate if I totaled a motorcycle every three or four years. Beverly Hills may have only two or three traffic fatalities annually, but I wouldn’t want to wade into any traffic death scene.

Officer Carra and Sergeant Munoz-Flores are obviously proud of being Beverly Hills police officers. They both enjoy riding motorcycles and, if nothing else, we have that in common, but there isn’t a paycheck big enough to lure me into a profession that would have me cleaning up and controlling highway carnage, risking my life in “two or three near misses a day,” and dealing with some of “the worst parts of society.”

The next time I get pulled over by a motorcycle officer, I am still going to try to talk my way out of a ticket, but I’ll wish him well, even if he still writes me up.

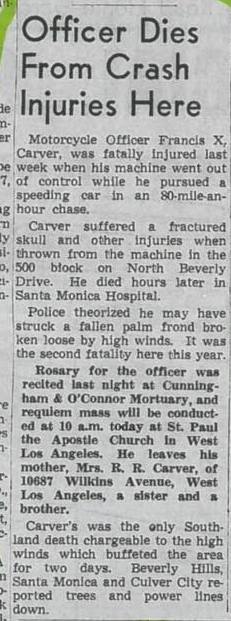

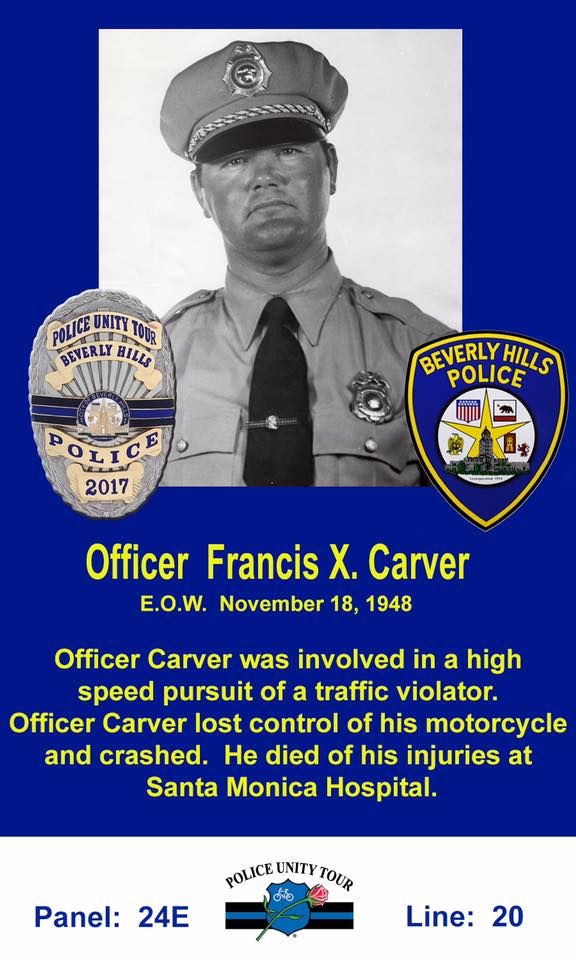

EOW: November 18, 1948

Information and Photos provided by Beverly Hills, CA Police Department Public Information Office.

Beverly Hills Cop, Too, Rider Magazine November 1987, By Davis Lester. Reproduced with permission by Rider Magazine and the Beverly Hills, CA Police Department